Introduction: Fish and farmers thriving five years later

The Fisher Slough Marsh restoration project serves as an example of what can be achieved when conservationists, farmers, and tribes work together. This project is recovering salmon, protecting surrounding farmland and roads from floods, and creating a more resilient community. Explore the timeline to see photos and maps of the Fisher Slough Marsh restoration project and learn about the site—then, now, and into the future.

Tribal traditions

The Skagit River Delta has supported people for thousands of years. Several tribes fished the waters of Puget Sound and the Skagit River, enjoying the historic abundance of salmon, steelhead, and other traditional food sources. In 1855, territorial Governor Isaac Stevens signed the Treaty of Point Elliott with western Washington tribes, which guaranteed their fishing rights in perpetuity.

Today, people from the Swinomish, Upper Skagit, Stillaguamish, Sauk-Suiattle, and Tulalip Tribes continue to fish and enjoy the Skagit River as an important part of their cultural heritage. They have also taken leadership roles in helping to preserve and improve the health of the river.

Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission

The 1800s: Farming changes the landscape

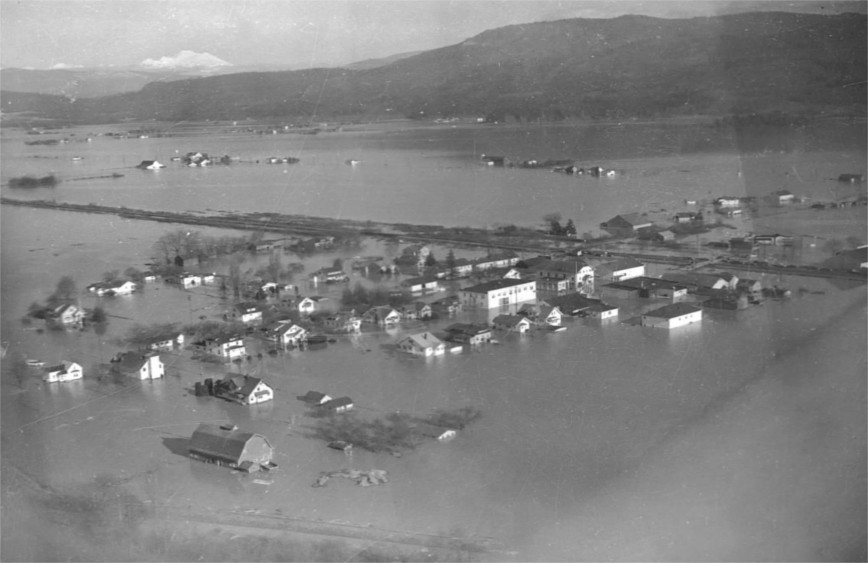

Farmers appreciated the fertile soils and mild winters of the delta. They installed diking and drainage systems in the 1880s to create more farmland and to protect communities and agricultural fields from river floods and tidal flows. However, winter and springtime flooding was a persistent problem for farmers and residents.

Margaret Willis

The 1900s: Flooding increases while fish populations decline

These drainage systems could protect the community and its farmland from minor floods, but larger floods were still a problem. They also required ongoing and costly maintenance. At the same time, populations of Chinook and other salmon species began to decline, in part because of the changes and restrictions to their habitat from these structures.

Concern about declining salmon populations and the listing of several species under the Endangered Species Act led to ongoing conflict between farmers and others interested in salmon.

Whatcom Historical Museum

2004: Mr. Smith's proposal

In 2004, Richard Smith—a local farmer—approached The Nature Conservancy with a proposal: if they would design a project that would benefit farmers and fish, he would sell them the land. That pact kick-started the Fisher Slough project, which received funding from numerous state and federal agencies, as well as private donors and foundations. The largest contribution would come in 2009.

2005: Choosing the ideal site

The Skagit River is an important migration corridor for salmon, and Fisher Slough is a quiet place for them to pull off the main channel to feed and grow bigger. Before, when the river rose, water frequently spilled over the old dikes onto neighboring land and roads. Setting back the dikes and restoring marshland would create a bigger “bathtub” to store floodwaters.

The goal of the project was to benefit both farmers and fish by:

- re-creating lost fish habitat,

- improving fish access to new habitat and to existing habitat upstream, and

- improving drainage and flood protection for farmers.

Marlin Green / One Earth Images

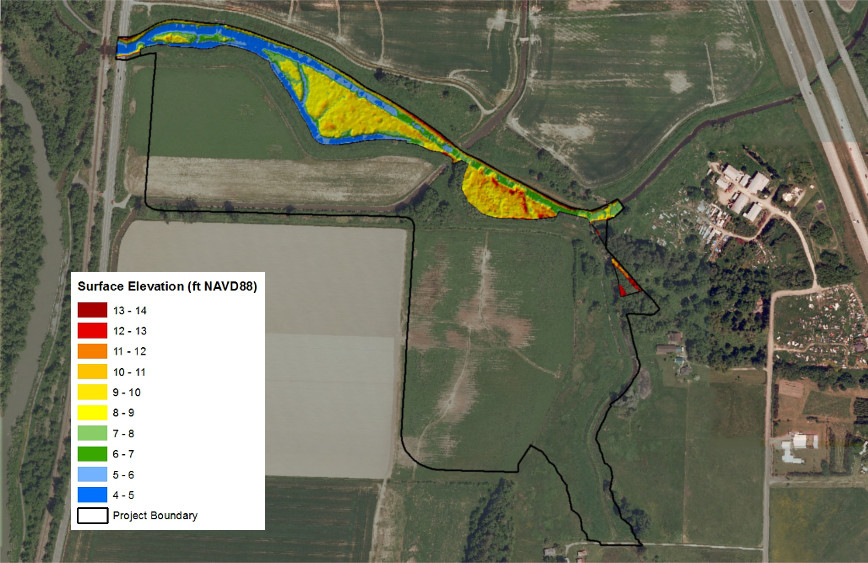

2009: Work begins

In 2009, NOAA awarded $5.7 million of Recovery Act funding to The Nature Conservancy (TNC) to restore the Fisher Slough marsh site.

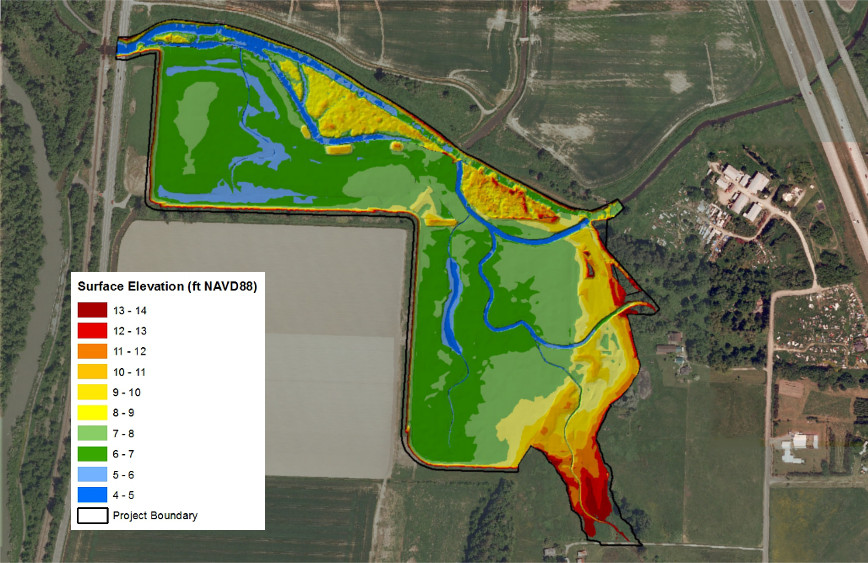

Construction began in the fall of 2009, when a series of self-regulating tide gates was installed to improve salmon access to Fisher Slough. Over the next two years, workers removed the old levee. They built a new one, set back from the original, which allowed more room for habitat, floodwater storage, and natural tidal flows.

They also dug tidal channels through the new marsh and replanted the site. Scientists predicted that an additional 16,400 young Chinook salmon would be added to the population every year as a result of the restored habitat. The project also created local jobs, employing 300 workers from 22 businesses.

Jenny Baker / The Nature Conservancy

2014: Success for fish

Fish are benefiting even more from the restoration than expected. Ecological surveys indicate that the site can support as many as 21,800 juvenile Chinook salmon—5,000 more than we had hoped for.

Roger Tabor / U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

In the future: Success for farmers and the community

Research on the social and economic benefits of the project suggest that the

$8 million invested in restoration will save the community $9-$21 million

over the next 50 years, reducing flooding on as many as 600 acres nearby.

This translates to:

- less flood damage,

- better farming opportunities,

- reduced maintenance and operation costs,

- good community relationships, and

- lower costs for future projects like this one because of the skills and knowledge the community has gained.